Coral 101: Spawning

Harriet Tyley

The first coral spawning was witnessed by scientists in 1981, and since then it has fascinated many. Corals spawn once a year following a full moon, releasing millions of gametes into the ocean in order to reproduce. Corals can reproduce sexually or asexually, and can be brood or broadcast spawners.

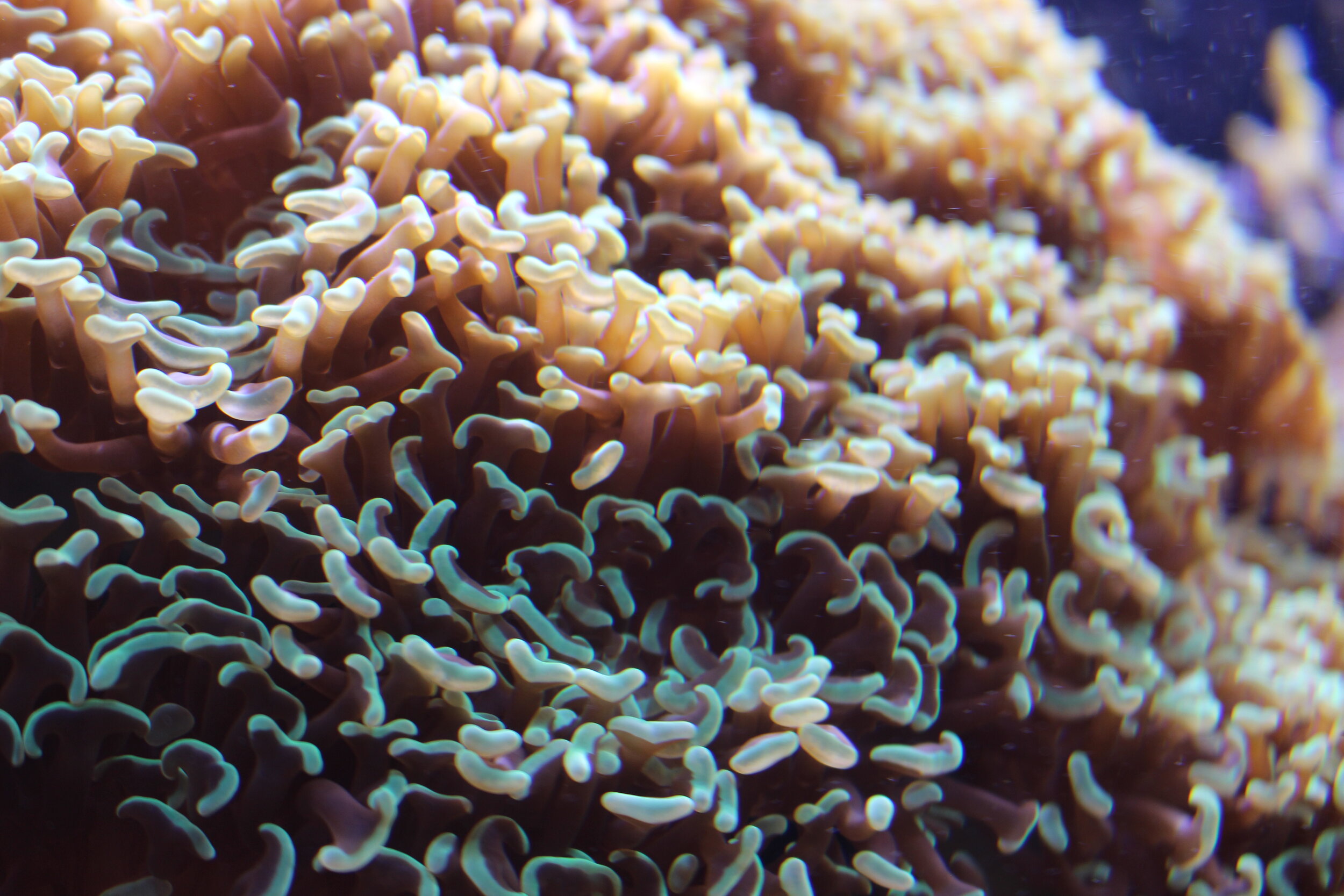

These beautiful creatures, corals, reproduce via a method called spawning. Photo: Harriet Tyley @harriettyley

Asexual reproduction

Fragmentation is an asexual method of reproduction, which involves the snapping of coral pieces (usually towards the tips) in sexually mature corals. These coral ‘frags’ are dispersed by water currents and storm surges, eventually settling and propagating. The more a coral is fragmented the weaker it becomes. There is an optimum rate of fragmentation, which is why climate change and the related increases in storm prevalence are posing a threat to many species of fragmenting corals. Under ‘normal’ reef environments, coral fragging allows dispersion of coral to new areas of the reef, where they can establish new reef systems over time. This method of asexual reproduction is found in hard stony corals, such as Acropora spp.

Sexual reproduction

Corals can also reproduce sexually, with the production of gametes and zygotes. During fertilisation, gametes (egg and sperm) fuse together creating a zygote. A zygote contains genetic information made up of half of each ‘parent cell’ gamete. Corals can produce both eggs and sperm (hermaphrodites), or produce only one gamete (gonochric). However, most colonies produce either male or female gametes rather than mixed.

Increases in storm prevalence due to climate change can affect coral fragging and so damage these beautiful landscapes. Image: Unsplash

In broadcasting species, these gametes are released by polyps directly into the water column and rise towards the water surface where they mix with other gametes and hopefully become fertilised. Successfully fertilised gametes will develop into planula larvae.

In brooding corals, fertilisation occurs within the polyp, where the gametes merge and create a planula larva. This planula develops within the mother polyp, and is released into the water column through the polyp mouth when it is developed.

Planula larva are positively phototactic (meaning that they are naturally attracted towards light) and swim towards the surface waters, where they are carried with the currents. This is a particularly dangerous period for planula larva, and the majority of them will be eaten by predators. Those that do survive sink back to the floor of the ocean and settle, attaching themselves to a hard surface. Now coral planula can begin metamorphosis and begin to develop into a polyp. Over time, coral polyps divide themselves by creating genetic copies which are identical, and this grows and grows until a coral colony forms.